Mobilising for sustainability: How a 30-day challenge is changing lives (and the climate)

Over the next several weeks, Future Earth will be rolling out a blog series called “Mobilising for sustainability.” We’ll be highlighting people, programmes and technologies from around the world that seek to build new ways of bringing non-traditional groups, including young people, hackers and more, into sustainability research – and in generating new solutions for the challenges of today. We encourage you to share your own examples of efforts to create momentum toward global sustainability in the comments section below and on Facebook and Twitter.

Read other stories in this series about summer programmes, hackathons and online education.

During a routine visit to Facebook, a post piqued Inger’s interest: A 30-day experiment that makes use of the most powerful solution to climate change that exists. People.

She was intrigued. Two years earlier she had decided she needed a change of scenery and pace. She quit her job at the Norwegian Embassy in London and moved to a small village in the English countryside to write a book about how she stopped shopping for a year. Inger, now deep into her book project, liked the sound of a month-long experiment. “Certainly sounds a lot easier than a 12-month one,” she thought.

Clicking on the Facebook post took her to the website of a project called cCHALLENGE. There she learned more about the experiment it offered: the programme would virtually connect 20 people from across the world who each had committed to make a small change in their lives and help them to reflect on and share their experiences along the way. The ultimate goal is to help ordinary citizens to combat climate change – but through a non-traditional route.

Inger hesitated: “I'm already a vegetarian. I have cut down considerably on plastics and packaging, and I went a whole year without shopping. What more can one person do? Be vegan? Fly less? Turn off the power?”

But then she realised that working on her book meant she was not taking much time to explore her rural surroundings. So she pledged to spend one hour each day in nature for 30 days.

Inger poses for a photo outdoors where she spent one hour a day for a month as part of her cCHALLENGE. Photo: Inger

At first glance, Inger’s challenge may seem like a purely environmental experiment. But by reflecting on one small, conscious change, she began to see how her actions were linked to habits, identities, social and cultural norms, rules, regulations and institutions, and how important these are for tackling climate change.

“I felt less hopeless. I began to see how small changes go a remarkably long way. I became more reflective and this has helped me become more resilient to challenges that life throws my way," she says.

It’s that sense of empowerment that makes cCHALLENGE different from the many campaigns that help people to reduce their carbon footprint. The project is organised by cCHANGE – a platform that’s been running for two years to help individuals and groups to see climate change from new perspectives.

“It is not about telling people to change. It is about developing a new perspective on change,” says Karen O’Brien, Professor of Human Geography at the University of Oslo and co-founder of cCHANGE.

All you need is 30 days?

It was Google engineer Matt Cutts who popularised the idea that all you need is 30 days to make a habit. However, a 2010 study shows that it actually takes about 66 days for a habit to stick. Breaking a bad habit is not so clear-cut.

"It's much easier to start doing something new than to stop doing something habitual without a replacement behaviour," says Elliot Berkman, Director of the Social and Affective Neuroscience laboratory at the University of Oregon.

"People who want to kick their habit for reasons that are aligned with their personal values will change their behaviour faster than people who are doing it for external reasons such as pressure from others.”

cCHALLENGE aims to present an empowering story on climate change, based on insights from research on transformations about engaging directly with personal, political and practical climate change solutions.

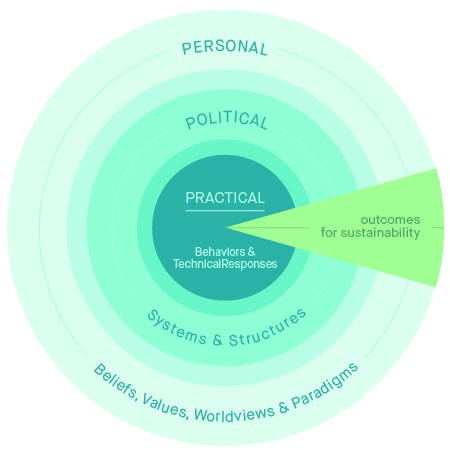

Together with Monica Sharma, former head of leadership and capacity development for the United Nations, and cCHANGE co-founder Linda Sygna, O’Brien developed a model called the “three spheres of transformation” that led to the formation of cChallenge.

The three spheres of transformation. Graphic: cChange

The “practical sphere” is where you see behaviors and technical solutions to climate change taking place.

“For example, transformations to low-carbon cities may involve lowering carbon emissions from automobiles and buses, by encouraging people to ride bicycles or use public transport,” says Sygna, a researcher at the University of Oslo and project leader of Future Earth Norway.

O’Brien argues that for too long climate change has been viewed as a technical problem, one that people believe will be solved with more expertise and technological innovation.

“If you treat climate change as just as a technical problem and are stuck in that practical sphere, you are going to fail. Such transformations are often impeded by political systems and structures.”

It is in this “political sphere” where transformations can challenge the vested interests and power relations that keep these systems and structures intact.

“For example, collective action to establish more bike lanes and showering facilities at work may facilitate a larger interest in bicycle transport,” Sygna says. However, this sphere is also where the conflicts arise.

The “personal sphere” includes individual and collective beliefs, values and worldviews that shape the ways that the systems and structures are viewed and influence what types of solutions are considered “possible."

cChallenges take place in the practical sphere but it’s the regular journaling and reflection over the 30-day period that helps participants understand the personal and political structures that they or society have built to impede change, and find ways to overcome them.

“Participants realise that it is more than just that practical sphere and their individual behaviour that matters. At different points in the programme, they realize that they can influence systems and structures, including social norms and political decisions. A key here is to recognize the roles that different beliefs, values and worldviews play in the political and practical spheres,” says O’Brien, who is also a member of the Future Earth Science Committee.

“For example, in one of our early pilot projects, the leader of a large environmental organization committed his family to not eating meat five days a week. He started to see how this experiment influenced friends, neighbours and members of his organisation. It challenged many of his assumptions about how easy it is to be ‘green’ yet drew attention to people’s willingness to engage with change. Participants usually discover that the conversations we have with others about change can make a real difference.

“Self-help books fly off the shelf because people are very interested in making their lives better. The climate change books just sit there. But climate change is probably one of the biggest self-help stories out there – we just haven’t been framing it that way.”

The point at which cCHALLENGE participants have their “a-ha moment,” such as recognition that they have the power to make change, varies, Sygna says, and so it is important that the programme design is flexible: “People always get something out of it that they didn’t expect. In fact, it’s often through failure or frustration that those moments come.”

People as a climate solution

Milda Jonusaite Nordbø is a 29-year-old woman living in Oslo. She had become concerned about the consumerist lifestyle being “sold” to young Norwegians, so her cCHALLENGE was to live on 50 kroner (6 USD) a day.

And each day of the cChallenge, a new email arrived in Nordbø’s inbox. Sometimes the emails posed questions: How are systems pushing back? How do you meet social norms? How do your own beliefs get in your way? How do you sabotage yourself by some of these beliefs that you’re actually not even aware of?

Sometimes the emails contained little gems of inspiration and links to resources, such as an animation on a technique called “outrospection.” Recognizing the importance of challenging outdated social norms and rules, Nordbø started to consider new ways to generate the collective empathy needed for social transformations.

All of the correspondence encouraged her to reflect on and share her experiences on her personal cCHALLENGE webpage. Writing these short blog posts about her experiences helped Nordbø see patterns and gain deeper insight.

“I learned that I can change and that my change does not happen in a vacuum. People see and hear what I do and while my actions are small, each action is a vote. So each time I spend a krone I vote for the production, transport, storage, marketing, consumption and waste of that product or service. I feel much more ‘powerful’ now that I have realised how much my small actions matter,” she says.

The cCHALLENGE evolved from a student assignment in a masters course on global environmental change, and O’Brien is keen to roll out cCHALLENGE to the next generation, starting in Norwegian classrooms.

"Young people are seeing connections that others do not recognize – that poverty, environment, justice and wellbeing are very much connected,” O’Brien says. They are open to challenging what the rest of us take as a given, but they need to see that their role goes beyond their individual actions.

“At least in Norway, we don’t give young people the idea that they are leaders, too. They think that leaders are only people high up in government. We need to start to change that narrative and show them that they are also leaders. I think it’s very empowering when you realize that your voice does count.”

“There is so much energy, so much potential in young people. It’s very hard to change people who have been doing things for thirty years – they might have little a-ha moments, but it’s often not as easy… You often get push back and nobody wants to be changed. But give young people the tools to actually empower themselves to create those changes in all three spheres of transformation… that’s where the solutions really lie.”

We’re all in this together

Fifty-four people have completed cCHALLENGE so far – from politicians, to celebrities to students – connected in small groups on a web platform. Most talk about how wonderful it was to be in a community of others going through the same experience.

“Following the journey of other participants by reading their blogs was heart-warming. We were in this together. Even though we all lived far apart. It was like belonging to a tribe of like-minded people. I could feel the support across the pond and that made it easier to complete my challenge,” Inger says.

O’Brien and Sygna are gearing to roll out cCHALLENGE globally and run a series of workshops to further empower and grow the community. It is also part of a new research project on the role of empowerment in adaptation and transformation.

“One of our goals is to see people like journalists take the cChallenge; UN diplomats taking the cChallenge; CEOs taking the cCHALLENGE; football players taking cChallenge; world chefs taking the cChallenge so this awareness is spread to many different groups of people.”

Will they need to change their strategy to target people who are more immune to change?

“My experience is that people really want to be able to do something and they feel so disempowered. When people engage with change, they become less fearful of it. If I’m a restaurant chef, I’m going to get organic food. If I’m a principal of an elementary school, I’m going to ensure the buses run regularly. Everybody can actually find out where they can make that difference. And I think that’s the really exciting part: to really just empower people as a solution to collective and systemic problems,” O’Brien says.

DATE

July 18, 2016AUTHOR

Michelle KovacevicSHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Spotlight on LMICs – Tired of Breathing in Pollutants? Time for Better Fuel Economy and Vehicle Standards

Future Earth Taipei Holds 2024 Annual Symposium

Spotlight on LMICs – The Future’s Juggernaut: Positioning Research as Anchors for Environmental Health