Blogging from an international workshop on climate and water

As experts strive to protect both cities and wild spaces from flooding, pollution and other risks, they are increasingly turning to an unlikely source for inspiration: nature itself. That’s the idea behind “nature-based solutions,” an approach to addressing environmental problems that looks to ecosystems to find potential fixes – from mangrove forests that buffer coastlines against storm surges to wetland grasses that filter heavy metals out of the water column.

Nature-based solutions were the focus of an international water and climate workshop that ran from 20 to 22 September in Paris. Three interns from Future Earth’s hub in Paris – Anastasia Cojocaru, Lizi Chen and Vincent Virat – attended this event and have written about their experiences.

You can read their blogs, delving into wetland restoration, flamingo habitats and flooding in cities in Southeast Asia, below:

Anastasia Cojocaru: “Visiting the Episy Marsh: Restoration and sustainable management of a wetland”

Lizi Chen: “Fighting flooding in Bien Mat”

Vincent Virat: “Climate change and nature-based solutions: A story from France”

Visiting the Episy Marsh: Restoration and sustainable management of a wetland

Photos and story by Anastasia Cojocaru

Living in Paris is challenging for me; it’s fast-paced and intense. But on a recent trip to a site called Episy marsh, I got to escape the city. I was surrounded by birds chirping. I could smell the moist ground, and all I saw was green, apart from a couple of trees with leaves that had changed colour for Autumn.

The entrance to Episy marsh.

The entrance to Episy marsh.

This opportunity came when I attended an international workshop on water and climate called “Ecological engineering and climate risks,” which took place from 20 to 22 September in Paris. It was a fantastic opportunity to explore how researchers and resource managers address environmental problems through solutions inspired by nature. This occasion brought together 220 participants: students, researchers and other leaders in the fields of water, biodiversity, cooperation and territorial development. For more details on the entire conference, click here.

On the third day of the conference, I participated in a trip that immersed me and several others into the restoration and sustainable management of a wetland, the Episy marsh. This marsh sits south of Paris, next to Fontainebleau. It was an exciting opportunity because, after spending two days in a conference room listening to scientists talk, I got to see how solving environmental problems through solutions inspired by nature happens in practice. After the visit, I had a deeper insight into what implementing these solutions is like from the challenges and accomplishments that I observed in the marsh.

Field trip participants check out a map of the marsh.

The Episy natural site is an original patchwork consisting of a pond, wet meadows, bogs and reeds. This conservation area is recognised worldwide, and it has been known since the 18th century among botanists. Two-thirds of the population of dragonflies in the Île-de-France region can be found here. You can also see abundant amphibians, butterflies, snails and vipers. Due to its exceptional fauna and flora, the Episy marsh acquired the status of a Natura 2000 site. But despite the fact that it is a national treasure, this marsh has had a fraught history.

The marsh patchwork.

The marsh’s northern part was a garbage dump in the 1960s, and 80% of the natural site vanished in the 1970s as a nearby quarry expanded. These disruptions have resulted in the reduction of the clay layer that once covered the marsh. Its water table has also lowered, which then caused the site’s peaty soil to dry up. These changes have led to a regression and disappearance of the remarkable species and plant communities that once called this wetland home.

A device for measuring water level in the marsh.

In 1982 a Biotope decree, which is a regulatory instrument of the French Environmental Code, recognised the need to protect this marshland and save what was left of it. When local authorities started working on the area, the main objective was to restore the marsh to a wetland because its remaining parts had started to dry out.

First, the Seine-et-Marne Deparment of Île-de-France region worked to restore native plants like grasses to the remaining parts of this marsh. In the 1990s they isolated a couple of areas in order to work on them. They cleared out these areas, removing the bushes and trees that had taken over in recent decades, allowing previously-disappeared species to germinate in the peat. The species came back, and at the same time, people got more interested in the Episy marsh. Thousands of people from all over the world visit the marsh every year to admire its natural wonders in an area especially designed for visitors, which is also accessible to people with reduced mobility.

Visitors stroll through the marsh, observing the rich plant and animal life.

Next, came the hard work. The goal was to restore the way that water moved through this marsh. To do that, the restoration experts designed several strategies that increased the humidity of the marsh and added a new clay level to the soil.

The restoration team planted poplars throughout the marsh to keep water upstream. Moreover, they constructed a canal that brings water to the site, helping to keep the marsh wet. The water is pumped out of nearby ponds through a small canal using a windmill.

A channel brings water into the marsh.

But the work isn’t done. Today, the Seine-et-Marne Department still prevents small trees from invading the protected area. They leave other areas untouched because this allows plants to reproduce themselves.

The restoration process has been successful, with 80% of the marsh’s 14 hectares now meeting satisfactory ecological conditions. Practically, there was a 15% increase in the number of species living in the marsh and an overall increase in the vegetation there. Moreover, protected species like common cottongrass (Eriophorum polystachion) that were last observed on the Episy marsh in 1994 have reappeared on the site. For more information on the Episy marsh, please click here.

Poplar trees and other vegetation hold water in the marsh.

In my trip to Episy marsh, I saw how every little adjustment or change to the species and environmental factors in a wetland can have an impact on the entire ecosystem; a change in even a seemingly small detail can affect the fragile balance of the wetland. I also noticed how human intervention through solutions inspired by nature can work efficiently if people keep in mind that ecosystems are fragile and need a lengthy period of time to recover. Perturbing the balance of the ecosystem is facile, but restoring it takes much effort and time.

Fighting flooding in Bient Mat

by Lizi Chen

The international water and climate workshop on “Ecological Engineering and Climate Risks” was held in Paris from 20 to 22 September, 2017. The workshop was organised by the Seine-Normandy Water Agency and French Development Agency (AFD), and it attracted environmental policy-makers, researchers, students and practitioners. The key focus of the workshop was on using solutions found in nature to fight against water and climate-related risks. The three-day workshop included project presentations, working groups, poster sessions and a field visit.

A man walks through flooded streets in Bangkok, Thailand. Photo: Siriwat Sasoonthorn via Flickr

Coastal flooding in Asia

In the afternoon of the first day of the conference, participants split up into three working groups: 1) Urban territory with flood risks in Africa; 2) Urban territory with coastal flood risks in Asia; 3) Rural territory with droughts and erosion risks in the Mediterranean Region. I attended a four-hour discussion on flooding in Asia with eight assorted experts. Our conversation drew on a fictional city to explore the ways that people are making cities more resilient to incoming water.

Bien Mat

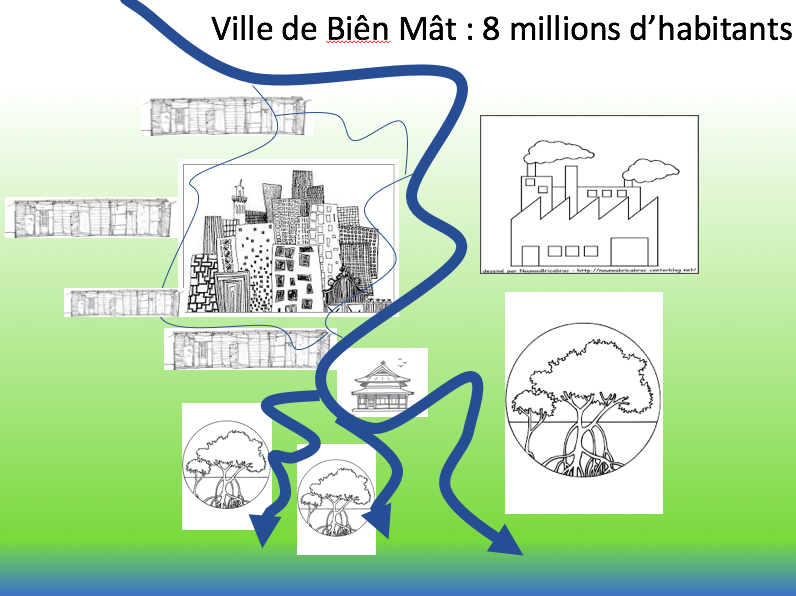

A fictitious city named Bien Mat is located in Southeast Asia, with a population of 8 million residents. Bien Mat sits on the Song River and is 15 kilometres from the coast.

A map of the fictional city of Bien Mat. Image: Nicolas Gratiot

With a subtropical climate, Bien Mat encounters many extreme natural risks, including droughts, sea level rise, typhoons and coastal flooding. Bien Mat has also spread rapidly in recent years, and the city has built a series of dams nearby. As a result, Bien Mat lacks the sediment, sludge and plants that might protect its shoreline from rising waters. Today 20% of the land in the city is threatened by flooding. This kind of flooding can turn soils salty, drown mangroves and erode the coastline. Those risks will affect aquiculture quality, local infrastructure and public health. In the future, the sea level around the city is projected to rise by 80 centimetres by 2100. Although Bien Mat is a fictional city, the challenges that it faces are similar to issues affecting cities throughout Southeast Asia.

Solutions to coastal flooding in metropolises

When discussing possible solutions to relieving coastal flooding in Bien Mat, Nicolas Gratiot, a researcher at the Asian Center for the Research of Water (CARE) and an animator for the session, guided the working group in thinking about specific solutions targeted at different areas along the river: the upstream area, metropolis and coastal area. In each area, the group proposed “nature-based solutions” to deal with coastal flooding in a systematic way. Nature-based solutions are an ecological concept that revolve around tackling environmental challenges like climate change, land problems and water issues through ideas that come from nature. For example, planting “green roofs” on top of buildings can help to cool dense urban areas.

In the metropolis area of Bien Mat, Martin Perrot from the environmental company Seaboost proposed designing this urban area to work like a “sponge city.” That is the name for cities where the sewage system has been reconstructed to collect and drain large volumes of water, especially during the flood season — keeping water off of streets like a sponge. Marie-Adèle Guicharnaud, an environmental entrepreneur from Australl, pointed out that planting more urban vegetation could help the city to soak up water. From my experience living in China, I believe that the city of Qingdao is a good application of the concepts of a “sponge city” and nature-based solutions. It has an advanced sewage system with wide pipes that, in some cases, can accommodate a sedan. The city also has many green spaces that locals enjoy but can also help during flooding. While Qingdao is a coastal city, it has not experienced severe waterlogging for hundreds of years because of these adaptations.

People gather on a beach in Qingdao, China. Photo: Remko Tanis via Flickr

In Bien Mat’s coastal area, all of the participants in the discussion agreed that the city should restore a mangrove buffer zone to protect against typhoons and coastal flooding. When I was an undergraduate student, I volunteered at Zhuhai Mangrove Park in South China. The park is located on Qi’ao Island, and it is surrounded by South China Sea. In the mangrove park, there were many kinds of species that I never saw during my life in the city, such as fiddler crabs, hermit crabs, starfish and different birds.

Thinking about this experience, I suggested that Bien Mat selectively plant its mangroves depending on the direction of monsoon winds. In Asia, for example, monsoons come from the southeast in the summer, so there should be more mangroves in the southeastern corner of the city than in other areas. Yann Laurans, director of the Biodiversity programme at the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations, mentioned that a semi-artificial canal system could be built to keep water from collecting in the city. Guicharnaud also pointed out that the long-term involvement of local communities in maintaining the mangroves will be the key to solving the coastal flooding problem.

Barriers to nature-based solutions

The working group also discussed the barriers to implementing nature-based solutions. Perrot from Seaboost explained that the biggest barrier is acceptance among city residents. To build that acceptance, experts need to understand local psychological and cultural perspectives. They also have to respect the local environment, such as the unique climate and geography. For example, when dealing with coastal flooding in Malaysia, nature-based solutions need to be consistent with Islamic customs, as well as the country’s tropical climate.

Members of the discussion group present their conclusions on the second day of the conference. From left to right: Sylvaine Rols, Marie-Adèle Guichardnaud, Lizi Chen (with microphone). Photo: Vincent Virat.

Sylvaine Rols, an environment specialist at the European Investment Bank, explained that nature-based solutions are a long-term strategy. For that reason, these sorts of solutions may not be useful in combatting urgent extreme events, such as near-term typhoons and storms. She also mentioned that development banks only have limited budgets for infrastructure based on nature-based solutions because it takes a long time for these solutions to pay off.

Although Bien Mat isn’t real, it represents many coastal metropolises that face challenges from flooding and sea level rise. That is especially true for big cities in East and Southeast Asia like Bangkok and Hong Kong that experience a monsoon climate. Nature-based solutions have gained attention in recent years because they adopt sustainable and ecologically-friendly solutions to dealing with coastal flooding. However, these solutions should also accommodate other engineering or policy solutions. Despite the wealth of ideas that exist for protecting a city like Bien Mat from flooding, many barriers remain. It will take the combined efforts of researchers working together with municipal governments, non-governmental organisations and more, for these metropolises to survive future floods.

Climate change and nature-based solutions: A story from France

Last month, interns from Future Earth’s hub in Paris went to a three-day conference called the “International Workshop on Climate and Water.” The event brought together more than 200 researchers, specialists, managers, curious citizens and even a few students! It focused on nature-based solutions – using and recreating nature’s services in order to solve human issues. Project leaders gathered in a complex near the Eiffel Tower to present and exchange their ideas with the rest of the audience. From creating large artificial wetlands that purify Chinese waters to restoring mangroves that protect against coastal erosion in Suriname, the conference was solution-oriented and, in the end, inspirational.

The Camargue as seen from above. Photo: Jean Roche

One particular project captured my attention: the restoration of lagoons and salt marshes in Camargue, a beautiful region on the Mediterranean coast of France between the sea and the Rhône river, renowned for its rich wetlands. The case study was presented by Jean Jalbert, General Director of the Tour du Valat, a research institute for the conservation of wetlands in the Mediterranean region. The institute’s work has served as an example for the Mediterranean region and the rest of the world, notably for its decisive role in the signature of the 1971 Ramsar Convention on wetland preservation.

Indeed, the institute is known internationally for restoring pink flamingo habitat in the 1970s in the Camargue. At that time, pink flamingos had stopped breeding the Camargue due to habitat loss from human development. Tour du Valat researchers restored those lost habitats and successfully brought thousands of flamingos back to the region. Their mode of operation has been successfully replicated many times ever since in various Mediterranean countries.

Due in part to climate change, the Camargue is now facing new, interconnected challenges: rising sea levels, coastal erosion and increasing intrusion of saltwater from the nearby sea. Fortunately, the region is managed and largely protected by various conservation entities. National and regional reserves, as well as the Tour du Valat Estate, together form a conservation area that is more than 70 times the size of Central Park in New York City. This includes land that the French Coastal Conservatory acquired from the SALINS group, a large European salt-production company, between 2008 and 2012.

In face of the new challenges, the French Coastal Conservatory, the Camargue Regional Nature Park and the Tour du Valat joined forces to find ways of restoring wetlands that wouldn’t harm the environment or the local population. They sought a solution that would enhance the collective wellbeing through the restoration of the former SALINS site and its 6527 hectares of land, about a quarter of this conservation area.

Dry soil around the site of an old salt production facility in the Tour du Valat estate. Photo: Jean Jalbert

The former industrial site was home to extensive salt-pumping, which degraded the original ecosystem. As a result, the project’s first objective was to remove the aging facilities and restore the wetland’s natural hydrological cycle. That happened on its own: Due to rising sea levels, the old coastal seawalls that surrounded the site began to breach, releasing water back into the barren area. Allowing the coastline to retreat from the incoming water, rather than building larger seawalls to keep the sea at bay, was crucial to the success of the project.

As seawater filled the site, natural saltmarsh vegetation returned, as did a variety of wildlife, such as ducks, hibernating wading birds, young fish and migratory eels. This solution was, in the end, both quick and cheap, as nature did most of the work. It also ensured future resilience to climate change, as the area can now serve as a buffer against flooding. Tour du Valat researchers continue to monitor the restoration process, but it has so far been successful.

It would have been difficult to lead such a project without local support or “social acceptability.” In a recent phone call, Jalbert stressed that while support from politicians was important to the success of the project, that support only came once the public had mobilised. To reach out to these wider audiences, the project’s leaders expanded their planning to include not only the protected region, but a wider geographical area that included a nearby village and its surroundings.

Showing residents how the project could improve their economic wellbeing was crucial, Jalbert says. The nearby village Salin de Giraud had, in the last decades, lost jobs because of the shuttering of old factories. The restoration team is now consulting villagers in the creation of a “discovery trail” that will allow visitors to see and learn about the site. The hope is that the trail will build eco-tourism around in the region, bringing jobs and tourist dollars. By successfully stressing this point, project leaders managed to gain support from locals.

Tiny plants spring up in a wetland restoration area in the Tour du Valat estate. Photo: Jean Jalbert

In sum, the restoration project successfully secured support by involving public institutions, such as the conservatory that had purchased the SALINS land, and by providing scientific and technical staff, along with Tour du Valat’s vital expertise.

Nature-based solutions offer a humbling perspective on humanity’s relationship with nature. In cases like this wetland restoration project, we are encouraged to accept the power of nature and to use it, rather than fight it through walls and concrete, in building long-term resilience. This is only possible if we look at humans and nature as part of one global ecosystem and not as separate entities. In the end, as nature gradually reclaims the Salin de Giraud site, it will hopefully become another powerful symbol of the Camargue’s beauty.

DATE

October 19, 2017AUTHOR

Anastasia CojocaruLizi Chen

Vincent Virat

SHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Spotlight on LMICs – Tired of Breathing in Pollutants? Time for Better Fuel Economy and Vehicle Standards

Future Earth Taipei Holds 2024 Annual Symposium

Spotlight on LMICs – The Future’s Juggernaut: Positioning Research as Anchors for Environmental Health