The new science of cities? Four reasons we need networked knowledge

This week, the 9th World Urban Forum wrapped up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. On the heels of this impressive event, I’m reminded more than ever just how important it is that cities and people from all walks of life are working together to design solutions in the face of rapid urbanisation. This year’s forum was a healthy, inspiring display of innovation and collective action – from the local and regional government representatives that took to the stage in the plenaries to the many people who worked tirelessly to organise diverse workshops, trainings and side-events.

What echoed true in almost every presentation and session I attended was the call to share information, work together to design solutions and move policy and decision-making out of “silos.” It was inspiring and refreshing to hear so many affirm a commitment to such action, as it solidified for me just how important Knowledge-Action Networks are in supporting cities implementing the New Urban Agenda – an outcomes document that guides global and local efforts around urbanisation.

In that vein, I’m sharing four key reasons why we need networked knowledge in urban areas:

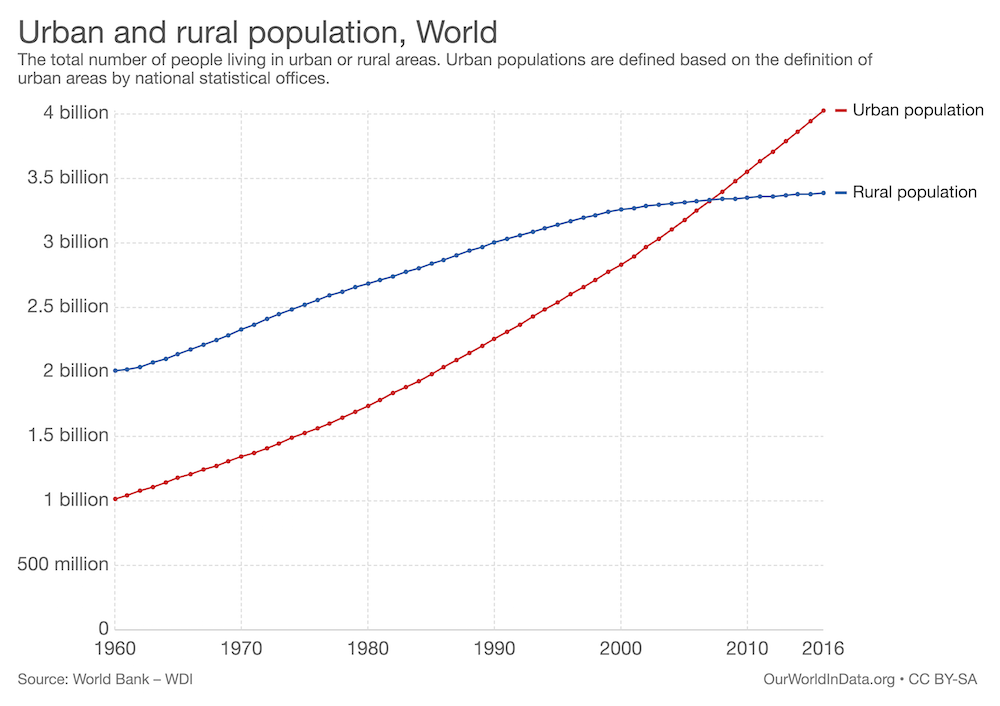

Roughly around 2007, the number of people living in urban areas around the world eclipsed rural populations. Graphic: Our World in Data

1. Rapid urbanisation

Over the past several decades, the evolution of cities has been brought on by a changing modern economy, rapid urban growth and a host of other factors. As a result, cities are increasingly powerful nodes in ever-more intertwined and global flows of people, capital, goods and information.

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) estimates that by 2050, roughly two-third of the world's population will be urban – making the next 30 years the scene of the largest human settlement transformation in human history. According to a recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), urban inhabitants will balloon from about 79% of the population in 2010 to 87% by 2050. In Asia, projections highlight a jump from 44% in 2010 to 64% in 2050.

With this higher concentration of people, we'll see the production of goods increase as consumption surges. We’ll power new industries, make more money and create new jobs, but we’ll also expend more energy, put greater pressure on the planet’s resources and produce more waste. Urban growth will also cost cities – a lot. In medium-sized cities, especially in the Global South where we expect to see the most rapid growth occur, city and national governments will spend an estimated 6 trillion USD to make room for new homes, areas for commerce and public spaces for growing populations. Some cities will build up and others will sprawl but, common to all, will be the challenge of meeting this massive demand for housing and living spaces in cities. How do we plan for this? Or maybe the first question we should ask ourselves is: What do we need to know to plan for this?

M'Lisa Colbert speaks at the 9th World Urban Forum in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Photo: UN-Habitat

2. Growing complexity

The complexity of the city landscape is that there are layers to it. Cities are first physical artifacts where people live and thrive amid the things we associate with cities: Tall buildings. Concrete. Glass. Freeways. Traffic. Noise. Subways. Bicycles. Parks. The list changes depending on which city you’re in. Paris is not Mumbai, and Tokyo is distinct from Bogotá. But woven within this exterior shell, the heartbeat of each city is its networks – those flows of people, capital, goods and information that make up urban life.

The more our cities grow, the more complex they become and the more sophisticated, efficient and sustainable they will need to be. They are rapidly changing. If we want our cities to be resilient to the challenges at hand and function in a more sustainable way, we need to learn about them as they change and generate new knowledge in support of the real-life challenges cities face. Part of this means transforming how we generate knowledge and plans. We need to move away from siloed approaches – where researchers are cut off from the people who make decisions about cities, and both are split into distinct departments or disciplines.

The disaster relief planning leading up to and after Hurricane Katrina is just one among many sobering reminders of how siloed approaches have failed cities in the past and have led to disastrous consequences. This hurricane slammed the Gulf Coast of the United States in 2005, forcing hundreds of thousands of people from their homes and revealing major breakdowns in infrastructure and disaster response.

3. Globalizing Cities

If cities are networks underneath it all, then it is going to take networks of people and organisations from all walks of life, with diverse knowledge-sets, to tap into cities to design and implement sustainable solutions. In recent years, we’ve seen a number of inspiring global initiatives work to support and unite cities: Future Earth’s Urban Knowledge-Action Network, C40, Cities Alliance, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, the Covenant of Mayors, 100 Resilient Cities, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and many others.

Many of these organisations were among those that led the creation of innovative sessions to facilitate learning and capacity building for the implementation of the New Urban Agenda, which was formally ratified at Habitat III in Quito, Ecuador. The New Urban Agenda impacts and involves a wide range of actors, including nation states, city and regional leaders, international organisations, United Nations programmes and civil society. This agenda also lays the groundwork for policies and approaches that will extend, and impact, urban futures.

Since Quito, various organisations have launched a wide range of exciting projects highlighting the efforts of cities to implement these ambitious goals. Among them, the Urban Knowledge-Action Network recently launched a project called “Nature in the Urban Century.” This is effort is a partnership with Stockholm Resilience Centre, The Nature Conservancy, the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICLEI and a diverse set of leading biodiversity and city experts. It seeks to develop solutions to the impact of rapid urban growth on biodiversity and essential ecosystems in and around cities.

Uniquely, the project team will develop scenarios and indicators, or strategies for envisioning possible futures and measuring goals, in collaboration and consultation with cities and regions around the world. These future scenarios will then support the creation of solutions in cities for key affected areas where biodiversity and ecosystems will be greatly impacted by the rapid expansion of cities.

4. Supporting sustainable cities

To support cities in their growing pains, we have to do more than just generate new knowledge. We will also need to mobilise communities and the capacities of urban experts and leaders – and do so in a way where we prioritise space for positive visioning of our urban futures.

We can’t ignore the fact that cities are facing monumental challenges. But we also need to be wary of the predominantly dystopian view of the future ubiquitous in news reports and popular culture. We can't envision healthy and sustainable cities if we're constantly being blindsided by doomsday scenarios. As the saying goes, “we act on what we know.” For example, if a central city planning office is making a large investment in the development of a wind or solar farm as part of a renewable energy transition plan, the city will need to rely on a lot of information and knowledge from a number of sources to make that plan a reality.

Networked knowledge can support such a city in bringing together the information they need to make good decisions. It opens links between diverse experts, such as a scientist whose work could reveal the impact of a proposed wind farm on local biodiversity and how to best plan around that, or local community members who have important information on how people use land in the area. It’s a way of making sustainable decision-making much more accessible for many different people. To put our best foot forward for the future of cities, we need to be more inclusive, open and creative in making sure information gets to where it needs to go. In return our cities will be more efficient, proactive and sustainable.

We need a new science of cities – and it needs to be networked.

DATE

February 14, 2018AUTHOR

M'Lisa ColbertSHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Spotlight on LMICs – Tired of Breathing in Pollutants? Time for Better Fuel Economy and Vehicle Standards

Future Earth Taipei Holds 2024 Annual Symposium

Spotlight on LMICs – The Future’s Juggernaut: Positioning Research as Anchors for Environmental Health