Berta Martín-López: The paradigm of nature’s contributions to people

Interview originally in Spanish, click here to read it.

Over 550 scientists from more than 100 countries warn that human well-being is at risk because biological diversity, the basis of our food, drinking water and energy, is in decline. Their concern is based on the four regional assessments on biodiversity and ecosystem services—covering the Americas, Asia, the Pacific, Africa, Europe and Central Asia—approved by the sixth session of the Plenary of IPBES (IPBES-6) that took place during the third week of March 2018 in Medellin, Colombia. The purpose of the Plenary was to build global agreements in an effort to solve the problems that put at risk the sustainability of life on the planet. To resolve this, scientists recommend the adoption of two new concepts: Nature's Contributions to People (NCP) and Indigenous and Local Knowledge (ILK).

To gain a better understanding of the concepts from the European and Central Asian perspective, Future Earth interviewed Dr Berta Martín-López over the internet. Dr Martín-López does not hesitate to affirm that along with nature, culture is an essential part of NCP and both contribute to improving human quality of life.

She emphasizes that "normally, those of us who opt for the NCP paradigm recognize that ecosystem services not only come from nature but are also co-produced by human capital and culture, knowledge and technology."

It should be noted that Berta is Coordinating Lead Author for Chapter 2 of the Regional Evaluation Report for Europe and Central Asia, and chapter editor of Deliverable 3(a). Outside of IPBES, Berta is Professor in Sustainability Science at the Institute of Ethics and Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research (IETSR) at the Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany, where she focuses her research on understanding and analyzing socio-ecological systems. In her research, she aims to understand the provision and use of ecosystem services as well as issues related to local knowledge and social perceptions linked to environmental behaviour and socio-ecological system governance. Berta was also one of the authors of the review of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), coordinated by the International Council for Science (ICSU) in 2015. In addition, she is a member of the Scientific Steering Committees of Future Earth's ecoSERVICES and Programme on Ecosystem Change and Society (PECS).

Berta reminds us that the well-being of humans is linked to our responsibility to use or make better use of the services nature provides.

PM: In terms of NCP, what are the key messages that you consider important to highlight?

BML: When the NCP paradigm came out, there were several reasons that led us to the conclusion that NCP are relevant. For example, if we only look at services that are considered beneficial to nature, we would ignore all the possible negative contributions of nature to human beings and among the negative issues, for example, we could consider the attack of carnivores on livestock or other animals important for humans. If we only consider ecosystem services, we are not being fair to the communities that are affected by such negative contributions.

BML: An element in the NCP paradigm is that we do not only look at the benefits but also the negative contributions and impacts. NCP can be considered as having a negative or positive impact on quality of life. For example, in the dialogue of ILK in Europe, wolves have a double role. Positive, because they eat the carcasses of dead animals. This is a benefit for the farmers because they do not have to pay to take away the carrion. The downside is that wolves may also attack their livestock. Therefore, farmers recognize this duality. And for me, this duality is the first point that is an advantage or a step forward in the NCP discourse.

After delving into the relationship of culture and its contribution to society immersed in nature, Berta, who has a PhD in Ecology and Environmental Sciences, emphasizes that within the framework of services some scientists from the humanities and social sciences, had not been involved in the subject until recently.

And she explains why:

BML: Culture permeates all ecosystem services. Food can be a provisioning service, it can be a material benefit, but food is also a cultural adaptation. The fact that we have different diets is a cultural adaptation. Recognizing that culture is transversal across services is likewise an advance of the NCP paradigm. Hence, we do not call cultural services as such in the NCP paradigm, but instead, we call them non-material contributions as opposed to the material contributions of nature."

BML: Another point that I find interesting has to do with ILK because the NCP paradigm recognizes ILK in the evaluation of services. I am referring to the terms context-specific and generalizing perspectives. It is a generalizing perspective when we try to make comparative assessments of ecosystem services or NCP that are analytical in purpose. But we also recognize that there is a context-specific view, acknowledging that NCP do not necessarily fit into the classification of material, regulating or non-material contributions. On the contrary, it represents the worldviews of some indigenous communities or, for example, farmers and shepherds with whom I work, who have a much more holistic approach of the relationships between humans and nature. They are unable to highlight a service over others because they understand that food derived from traditional and extensive agriculture requires water regulation, soil fertility, erosion control or pollination; and altogether makes a whole.

BML: The context-specific perspective aims to respect these more holistic views and especially in some indigenous communities where mother earth or nature is a being in itself. But we also recognize that there may be hybrid approaches. And, for example, we have done it in the European and Central Asian region. We took the dialogues of ILK and analyzed them carefully to fit the narrative of shepherds to the list that we had in the generalizing perspective, resulting in an analysis of the NCP based on the ILK.

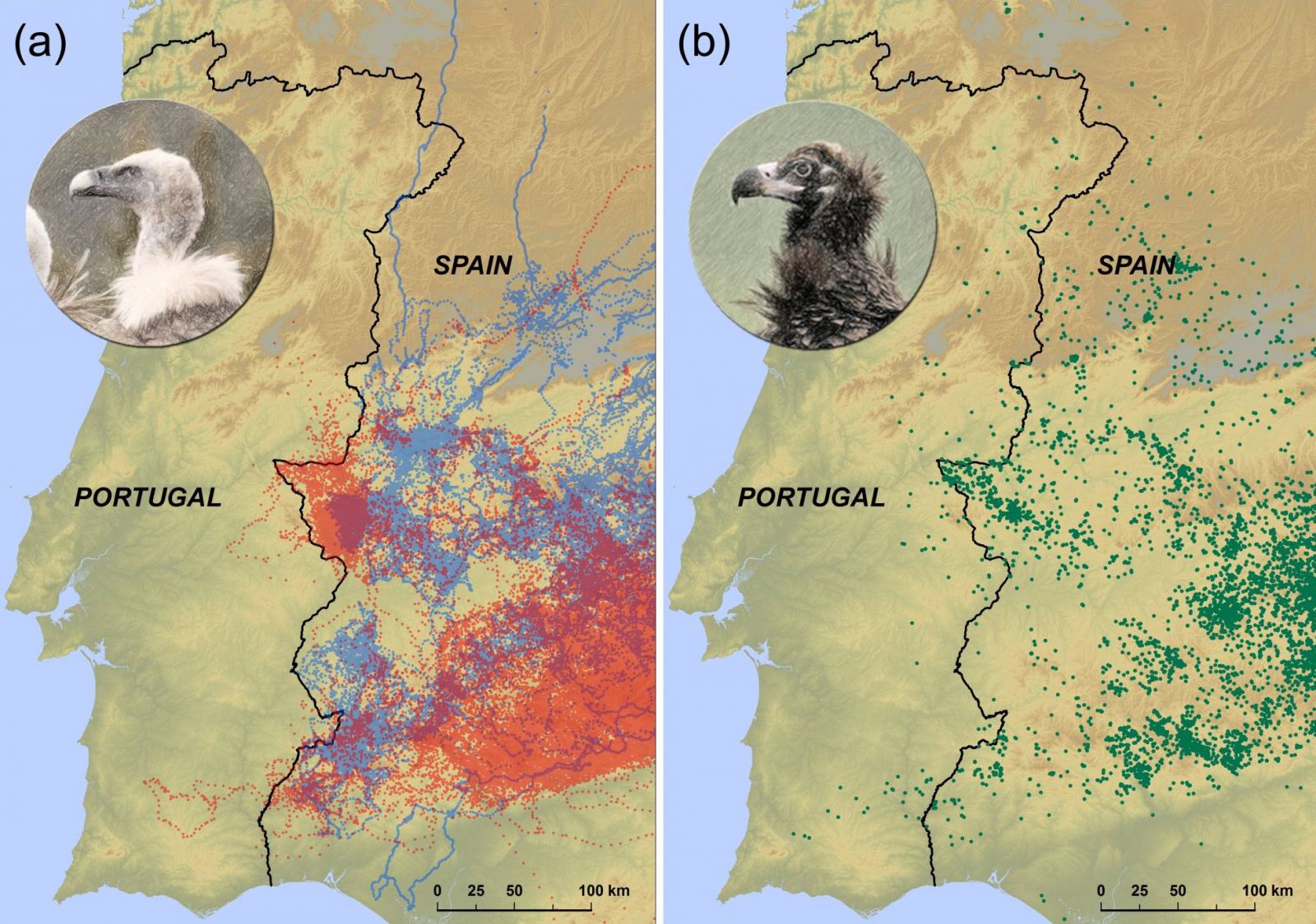

BML: In summary, it gives much more flexibility and there is a scientific background that supports it. And this brings me to a point that is my previous experience of having made other ecosystem service assessments, such as the Spanish Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and in all my research work. Reading the ILK dialogues in Europe and Central Asia, made me realize the importance of the NCP paradigm. In these dialogues, the herders highlighted two aspects that I had never considered in my research on ecosystem services because they simply do not appear on the predefined lists of ecosystem services, such as the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), the list of the projects of The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), and the Common International Classifications of Ecosystem Services (CICES) list. These two benefits are the role of vultures for carrion removal, as well as the role of guard dogs to protect livestock from wolves. We included these two services in the IPBES evaluation of Europe and Central Asia, which had not been done before. Furthermore, by doing so we brought to the table two benefits that until now had not been evaluated and, by doing so we facilitate giving a voice to these farmers and herders. And this has implications for equity as we acknowledge other voices, other views.

BML: On the other hand, the inclusion of these benefits as NCP has political relevance. For example, the European Union (EU) platform for coexistence between carnivores and humans recognize guard dogs as a relevant tool to mitigate conflicts between humans and carnivores. If we do not have an assessment of the importance of guard dogs and the trend of their populations (which has tended to decrease due to rural abandonment and the fact that a few years ago [herders] did not need these guard dogs due to the scarce populations of wolves), we cannot propose management measures for the coexistence between humans and large carnivores.

BML: The associated knowledge on how to breed guard dogs, take care and educate them, has also been lost. If we had realized that these benefits existed, we would have maintained them, we would have preserved them.

BML: On the other hand, for the other service of carcass removal, the lack of its knowledge as service might have consequences for policy, as it is illustrated in the context of the Iberian Peninsula. A few weeks ago, an article was published in Biological Conservation that showed how different species of vultures do not cross the political border between Spain and Portugal. Their distribution fits perfectly with the political frontier. In Portugal, in the last 10 years, the populations of vultures have declined abruptly. Well, how is it that vultures do not cross the political border? Because while in Spain it is allowed to leave the carrion in the field, in Portugal it is not allowed for sanitary reasons—in order to prevent the mad cow disease (or Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy). Vultures do not cross the border because they cannot find the same resources on the other side of the border that is Portugal. This also has other impacts beyond vulture populations: if there are no vultures, the carrion of other animals, such as ungulates, is not eliminated, and if there are no vultures we have to pay companies to eliminate the carrion. This demonstrates that negative consequences of not considering vultures as providers of ecosystem services can have negative impacts not only in nature but also in society. The IPBES experience in evaluating NCP in Europe and Central Asia has made me realize the importance of approaching ecosystem services from a different view, without a preconceived list of ecosystem services, in order to discover new benefits of nature, which until now had not been considered as such.

The Summary for Policymakers (SPM) on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Europe and Central Asia approved by IPBES-6, highlighted that until now, the efforts to conserve biodiversity in the region have not been sufficient. The document emphasizes that increased conservation efforts and sustainability of the use of biodiversity would increase the chances of meeting national and international biodiversity objectives. However, this is complicated because, generally, economic growth is not decoupled from environmental degradation. This entails the obligation to adopt a transformation in tax policies and reforms throughout the region.

PM: Why do you think the concept of NCP is important and, in your opinion, what does this represent for the future of research and for the community of researchers at the global level?

BML: What it represents is that we have much more flexibility and thanks to recognizing the two approaches, the generalizing and the context-specific, marginalized communities that are directly affected by the deterioration of nature may be able to have a voice in the decision-making process. And they can have a voice highlighting the importance of nature for their societies. In my opinion, in the future of the research of the NCP or ecosystem services, or the relationships between humans and nature, this could be one of the lines we must investigate. This means researching equity and justice, both procedural and distributive equity. Because if we are able to attract more voices, we will also be able to evaluate how these benefits of nature or how the damages of nature are distributed among social actors. And really see who deals with the burden and who with the benefits. And from there, we might be able to design policies that not only favour the conservation of biodiversity but promote eco-social equity.

PM: And, in your opinion, how can this procedural equity be implemented?

BML: In the theory of environmental justice there are three levels of equity: the first is recognition and, I believe, with NCP, one can at least raise this awareness of how indigenous communities or local communities relate with nature and how they benefit from nature or how many of these negative contributions of nature fall upon them. That is the first thing. For example, in some European countries, where we are seeing an increase in the forest area, we can acknowledge that this is not because we have lowered our consumption of natural resources, on the contrary, it is because we are externalizing our consumption and depleting natural resources of other countries.

BML: The other example is based on my experience in Spain. We worked with farmers in extensive farming systems who kept terraces in a steep mountain in a semi-arid area of the Sierra Nevada. These farmers made efforts to keep the terraces and acequias (i.e. irrigation ditches) that they inherited from the Arab period in Spain. These acequias are a very interesting system because they allow the filtration of water from the top of the mountain, where the snowfields are, to the aquifers. So that in summer they could have water even if it is a semi-arid place. But the acequias system was not only used for transporting water¸ they also favoured the riparian vegetation and the different species associated with aquatic components. This riparian vegetation also helped to increase soil fertility and water regulation. Yet, these farmers had not been heard in decision-making and, in fact, they were initially excluded from the management of the national park. Thanks to several projects such as the Mediterranean Mountain Landscapes Project (MEMOLA), or one where we developed an ecosystem services assessment by which we show the role of these ditches for habitat maintenance, water regulation, soil fertility and sustainable food production, the national park generated a working group to recover the local knowledge of the farmers and establish a restoration program of the acequias. Now farmers are taken into account in the decision-making process [within the park] and, not only that, a very good programme was developed, which recognizes their knowledge by involving them in the restoration of the acequias.

One of the many acequias restored in the Sierra Nevada, Spain. Photo: IDEAL y Waste Magazine.

One of the many acequias restored in the Sierra Nevada, Spain. Photo: IDEAL y Waste Magazine.

BML: This, for me, is an example of 'procedural equity' because [traditional farmers] have been given a voice and are being involved. The first thing we had to do was to show that the services were there; and the second thing was that there were some actors involved in its maintenance—the farmers. This is an example where through the evaluation of ecosystem services, one can support the implementation of 'procedural equity'. It could also be considered on a global scale, but from small examples, in different places, one can move towards procedural equity globally.

PM: In what year did this happen?

BML: The national park was created in 1999. We started the evaluation in 2007 and finished it in 2012. But it was around 2010 when they started with this local knowledge project of the acequias, publishing (in Spanish) the Manual del Acequiero.

PM: One can visualize the indigenous nations of Latin America or the indigenous and native people of Canada, but it seems to be difficult to recognize that there are still indigenous nations in Europe.

BML: In Europe, our indigenous people are not recognized as indigenous, except for the Sami people, but they are farmers and herders to an extent. They hold the local ecological knowledge that we have in Europe. And, unfortunately, in the IPBES evaluation of Europe and Central Asia, we found that their local ecological knowledge is disappearing and is not being transmitted generationally for many reasons. [Some causes are] the intensification of agriculture and livestock management and rural abandonment among other social issues. That knowledge is still kept by the oldest generation, and when they die that knowledge and heritage will die with them. I think it will be the saddest thing that can happen to the cultural landscapes of Europe.

PM: Of course, partly because it endangers these sustainable mechanisms that are also ancestral.

BML: These are ancestral, sustainable, and generate multiple contributions to nature. Not just one. These mechanisms not only produce food but regulate water and control erosion. These mechanisms work in a holistic way, working with all the processes that there may be.

PM: Acknowledging ILKs is indeed a much-needed innovation, but there is still a clash with scientific thinking, which tends to be traditionally conservative. It is a different ontology, and, in addition, it is a challenge due to the fact that local and indigenous nations require or need a more formal knowledge which is more associated with societies of a more reductionist thinking, such as the Western one. In your opinion, how do you think current and future researchers can connect these knowledge gaps?

BML: First of all, it is to say that local and indigenous knowledge in itself has value because it is a cultural heritage and that it does not always lead to sustainable practices. But simply the mere fact that it exists is a cultural heritage.

BML: Second, we can ponder every time we do research or whenever we practice any management policy on territories where these populations with local knowledge exist, about the possible implications that [our research] may have in these communities, both negative and positive. I refer to making a process of reflexivity, a process of positioning oneself as a researcher in this community and that we are clear and transparent about what it can mean for the community. I have witnessed—and I have even done it when I was younger—that [the researcher] goes, takes the data, publishes, and does not think about what impact of bringing a tape recorder or a camera, or the context of the questions in the interview may cause. Considering the consequences of our research and discussing it with the members of the community is necessary.

BML: On the other hand, I believe that the richest strategy that can generate resilience to environmental change is diversity. And not only diversity of species or ecosystem services, but also the diversity of knowledge. Both local knowledge and scientific knowledge are complementary and, as such, are hybridizing. I think it's much more valuable to be aware of how this hybridization is occurring and to be aware of what is lost or gained through this [process of] hybridization.

PM: What comments can you give us about your experience at IPBES-6?

BML: It was very interesting because one is suddenly aware of how a paradigm shift can generate resistance. But it has also been very interesting because it was possible to generate common understandings through dialogue and a process of co-production of knowledge with the delegates of the participating countries. The change brought by a paradigm shift led to resistance¸ but after days of discussions, constructive discussions, empathic listening, we managed to reach an agreement and it has been very constructive and very productive. It was a very good experience to be a part of this knowledge co-production process with the delegates as I had never experienced it before.

Photo: IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera.

Photo: IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera.

BML: And I think it has been, as I was saying, a model experience of what the science-policy interface is. Generally speaking, it was very positive.

PM: Resistance, in what sense?

BML: Well, in the sense that when one comes with, for example, the NCP as a new paradigm, it is introduced in some scenario where European countries have already adopted and included in their policies the concept of ecosystem services since a few years ago. This generates resistance because now, all of a sudden, it seems that they are being asked to adopt the concept of NCP. That generates an initial resistance. Through the process of coproduction of knowledge that took place in Medellin, it was understood that NCP do not replace the concept of ecosystem services. The idea is not to substitute, the idea is for the NCP to encompass ecosystem services.

PM: It intrigues me how these changes are unwrapping. It is a breakthrough of IPBES.

BML: I think it's wonderful. The issue of the ILK and the plurality of values and the idea of the NCP seems to me that it is truly breaking schemes.

After three years of development and around USD 5 million, the Regional Assessment Reports on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of IPBES have involved the review of thousands of scientific articles, as well as government reports and other sources of information, including indigenous and local knowledge. These documents represent the most important joint contributions of experts in this decade regarding the understanding of nature and its contributions to people, offering routes for future actions. To access the SPMs of the four regions, visit https://goo.gl/oJ4DRq. The full reports (including all data) will be published later in 2018.

DATE

April 18, 2018AUTHOR

Paula MonroySHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Spotlight on LMICs – Tired of Breathing in Pollutants? Time for Better Fuel Economy and Vehicle Standards

Future Earth Taipei Holds 2024 Annual Symposium

Spotlight on LMICs – The Future’s Juggernaut: Positioning Research as Anchors for Environmental Health