Meet the new postdoctoral researchers for PEGASuS 2: Ocean Sustainability

The two winning projects for PEGASuS 2: Ocean Sustainability are joined by two postdoctoral researchers: Dr. Erin Satterthwaite and Dr. Alfredo Giron. They will work with the projects under Future Earth at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis at the University of California, Santa Barbara. They will also participate in the Ocean Knowledge-Action Network and complete their own independent projects over the next 18 months.

Erin Satterthwaite and Alfredo Giron

To learn more about the two PEGASuS 2: Ocean Sustainability projects — “Defining the observing system for the world’s oceans – from microbes to whales,” and “Managing Ocean Change and Food Security: Implementing Palau’s National Marine Sanctuary” — more details are available here. And read more about Managing Ocean Change & Food Security in Palau and Keeping an eye on the world’s oceans: designing the a global ocean observing system to monitor marine life also on our blog.

Giron and Satterthwaite will soon be traveling to Copenhagen in May 2019 to attend the first Global Planning Meeting in preparation for the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, ahead of its launch in 2021, along with members of the Future Earth Ocean Knowledge-Action Network and many other thought-leaders and key stakeholders.

Giron received his doctorate in biological oceanography from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where he developed new methods to inform fisheries management, with focus on the Gulf of California, Mexico. In 2014, along with members of the Gulf of California Marine Program, he created dataMares, a science communication and data sharing platform. Today, dataMares is one of the leading outlets in Mexico for socio-environmental science communication. You can watch a video about some of his recent work here.

Alfredo Giron and Fabio Favoreto during a campaign to the Gulf of California in 2016 to monitor the health of rocky reefs in the region. Photo credit: Santiago Dominguez.

Satterthwaite was most recently a California State Sea Grant Fellow with the Environmental Research Division, a research unit of the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center. She received her doctorate in applied marine ecology and conservation in the Environmental Science and Policy Department at the Bodega Marine Laboratory, University of California, Davis. Satterthwaite also helped to develop an outreach program at Bodega Marine Laboratory, which exposes students to observation-based learning techniques, and has created a Coastal and Marine Science Pre-College Program at UC Davis.

We’re excited to have Giron and Satterthwaite with us here at Future Earth! Keep reading to learn more about their previous experiences, as well as what they will be working on during their time as postdoctoral researchers in Santa Barbara.

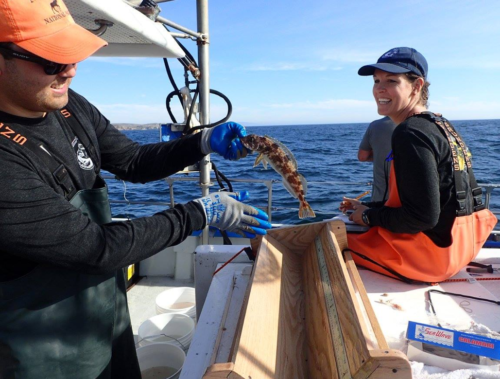

Erin Satterthwaite and Aaron Ninokawa admire a very tiny lingcod before measuring it for the California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program. Photo credit: Connor Dibble.

Kelsey Simpkins: Can you elaborate more on your previous ocean work and experiences? What are some of your recent accomplishments?

Alfredo Giron: I just defended on March 12 [2019] – one month ago! I was doing my Ph.D. at Scripps at UC San Diego. And I had two advisors, so I kind of had two research lives. One of them was Octavio Aburto, he works a lot with coastal communities in the Gulf of California. And my research was focused on trying to understand how sustainable are fisheries in the region, both from a stock assessment perspective, but also from the people’s perspective – I was trying to look at how much money they make and how it compares to global poverty levels.

My other advisor was George Sugihara, who is one of the founding fathers for bringing chaos theory into practical applications in ecology. By using his approach, I tried to improve some of the methods that we had been using to predict future populations of fish, and then to use that information in order to propose management strategies, tying it back to what I was doing with Octavio [Aburto].

[For my Ph.D.] in the end, what I tried to do was approach a single problem. In fisheries science, we have been trying to find the relationship between the number of adult fish and the number of juveniles next year. And that is really difficult to find, because the system has a lot of things that influence that relationship, right? Maybe the environment was not good that year, maybe the adults didn’t eat as much as they needed, there are many many things. So basically we had given up in trying to predict that, and fisheries management in many countries doesn’t even consider that relationship anymore. Some part of my Ph.D. was trying to show that that relationship actually exists, but that they methods that we had been using simply can’t account for all the variability. We need a different approach. And that’s why I was working with George Sugihara and one of his close colleagues, Steve Munch at UC Santa Cruz. And we did, at a global scale, we showed that we can predict recruitment – the number of juveniles – very well, by using these new methods. And then what I did was to take those methods and apply them to the sardine fishery in Mexico, so that we can better predict how many juveniles we’re going to have every year, and try to propose a management quota.

Erin Satterthwaite: In undergraduate I went to school on the East Coast, and I studied marine science abroad in India and the Galapagos. That was where I was inspired to work on global ocean sustainability issues – actually working on the ground with people helped me to see the complex nature of these social-ecological questions. After these experiences, I wanted to work on applied marine issues, so I went to graduate school to study marine science and policy in the Ecology program at UC Davis. At the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, my main interest was working on questions related to fisheries management and marine protected area design. I studied where juvenile marine animals start from and where they end up to understand how juveniles contribute to populations and how that varies along the West Coast. I also studied how plankton (all the drifters) communities change seasonally, with depth, and from nearshore to offshore along the coast of California and what specific processes drive those changes. These questions are important to understand how marine populations are connected along the coast which is essential for marine reserve design and management.

Another piece of my graduate work was helping to start the California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory. This program is a citizen science program where we partner with local charter fishing boats to take volunteer fishermen out to collect data on groundfish, like rockfish and lingcod, inside and outside of California marine protected areas to determine how the populations compare between protected areas and areas not protected. This was a really important project to me because I was able to engage with our local recreational fishermen, so the stakeholders themselves, in collecting data relevant to fisheries management. I really enjoyed the engagement aspect of this project and find that to be an important part of the work for me.

Most recently I was a fellow in the NOAA’s California Sea Grant State Fellows Program, where I worked in Monterey with the NOAA Environmental Research Division on research questions related to variability of marine life in the California Current Large Marine Ecosystem. In that work, I have been using environmental DNA and traditional sampling methods to better understand biodiversity patterns off the coast of California, scaling from the tiniest things like microbes and bacteria, up to top predators, things like whale and birds.

KS: What will you be working on with PEGASuS 2: Ocean Sustainability? What are you most excited about?

AG: I am going to be focusing primarily on the Palau project. What I have been doing so far is helping them with the broader scope of the project. The project is divided in three subgroups, and I am co-leading two of them with post-docs at the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions. I think it’s very rare that you have the opportunity to communicate with the people who are going to implement for real, the solutions, or the science. So I am very excited about getting to meet these people, getting to know what they really think science can contribute and just learning about matching the time scales at which this science has to happen and the implementation of the work.

ES: My primary project will be collaborating with the working group, Defining the observing system for the world’s oceans – from microbes to whales,which is working to coordinate a global ocean observing system for marine biodiversity. I’m especially excited for this project, because it’s very timely given that there’s a lot of momentum in the global arena around ocean sustainability issues. This project is working to build the foundation for a globally coordinated ocean observing system for biological variables, such as phytoplankton, zooplankton, fish, and turtles. The working group has been focusing on: what are the core components of a biological ocean observing system, how do we operationalize it, and how do we make derived products from the biological ocean observing system to inform socially relevant questions?

Right now we’re in the process of identifying who is currently collecting data around the globe on these various biological variables, such as phytoplankton, zooplankton, and fish, and then mapping where those monitoring efforts are happening in relation to the known distribution of each biological variable. So my first project will be mapping the global seagrass monitoring networks and looking at how those overlay onto the known seagrass distributions around the world in order to determine if we are monitoring a majority of the habitat or if there might there may be gaps in our monitoring efforts. I am really excited to collaborate with the working group and learn more about biological monitoring efforts happening at a global scale.

Maybe talking to a starfish? Maybe taking a photo of it? This is what Alfredo looks like when he has finished the duties for a scientific dive and has some extra air to explore around. Photo credit: Santiago Dominguez.

KS: What will your independent projects be about?

AG: Mine is trying to build a database on how prevalent is poverty in coastal communities around different countries, probably starting with Latin America.

ES: Mine is working with environmental DNA and traditional sampling methods to determine how reliable eDNA can be for understanding patterns of marine biodiversity, and then using that information to build indicators for ecosystems and ecosystem health.

KS: Why does being based in Santa Barbara for scientific work excite you?

AG: Santa Barbara is just this hub city for fisheries and social-ecological scientists. We have NCEAS, we have the Bren School [of Environmental Science and Management], and that is definitely something that I didn’t have in San Diego. Getting to work in person with all of these people and learning from them will be great.

ES: Being in Santa Barbara and being located at NCEAS excites me because of the community that I will be a part of. I’ve already felt at NCEAS that it fosters collaboration and such a warm, welcoming culture, which I think provides an amazing space and incubator for innovative sustainability solutions. Also, it is exciting to be in an environment where people from all over the world come together to address complex questions from unique perspectives. It’s a really dynamic team. Plus, it’s exciting being in Santa Barbara, on such a wonderful part of the coast, where a lot of environmental solutions are actually happening on the ground.

Erin in her element, seawater, collecting data for a coral reef restoration study conducted as part of a global partnership between University of California, Davis,Universitas Hasanuddin, and Mars Symbioscience in the Spermonde Archipelago of southwest Sulawesi, Indonesia. Photo Credit: Gabriel Ng.

KS: Where are you originally from? And what are you looking forward to about living in Santa Barbara?

ES: Actually, funny enough, I am from Santa Barbara originally. I never thought I would come full circle, but here I am! It’s funny the way life goes. I feel like I don’t know Santa Barbara as an adult so I’m excited to explore the area. Most of my free time is dedicated to outdoor adventures — I love anything related to surfing, diving, mushroom hunting, backpacking, mountain biking, really anything ocean or forest related. I also love bike tours, so I’m hoping to explore around here by bike. I also love celebrating life by dancing, cooking, and spending time with community! I’m really excited about getting to know Santa Barbara better.

AG: I’m originally from Mexico City. But now I feel so attached to the ocean, and there’s no ocean here [in Mexico City]. In my free time I love dancing – at some point in my life I was dancing like every night of the week, now it’s not as extreme. And I also like climbing, both indoor and outdoor climbing. And the third hobby that I have that I really really like is photography, so I try to mix them up!

PEGASuS 2: Ocean Sustainability, is a partnership between Future Earth,National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), and Global Biodiversity Center at Colorado State University. Our vision is to accelerate transformations to a more sustainable and equitable planet by drawing on collective knowledge. Recognizing that the research community on its own cannot adequately address these challenges, we are partnering to support two ocean sustainability working groups involving not only researchers, but also innovators in policy, business and civil society to generate research that meets society’s needs.

DATE

April 30, 2019AUTHOR

Alfredo GironErin Satterthwaite

Kelsey Simpkins

SHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Future Earth Members Join UN Ocean Conference in Barcelona

SOLAS Researchers Publish Special Feature on Air-Sea Interface in Changing Climate

Building a Knowledge Action Network In the Indigenous Communities of the South Pacific