Why Inclusive Science Communication Benefits All People

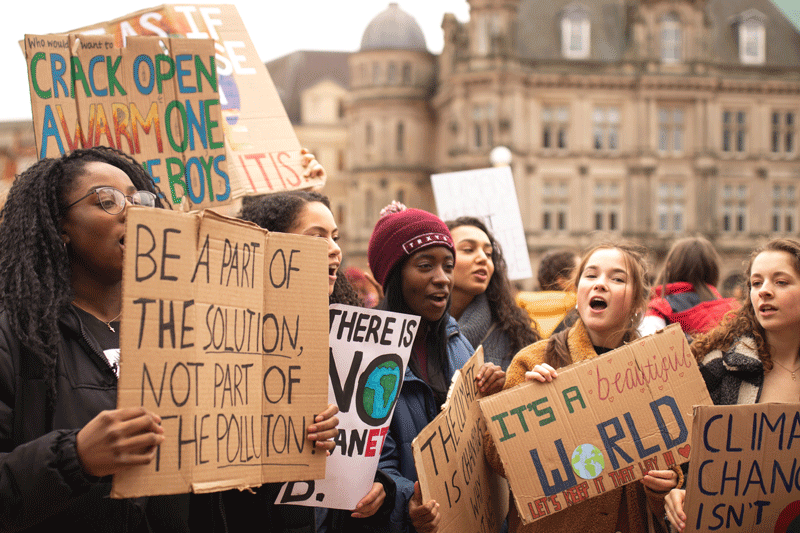

As more and more young people make connections between the climate crisis and its intersections with historic and structural racial and social justice issues, the question of how to do more inclusive science communication is one that has become central to all of my science communication classes.

More inclusive science communication that is based on environmental justice (EJ) practices seeks to make discrimination and disproportionately harmful impacts on marginalized groups more visible, and also lift up community agency and leadership in response to such impacts. Centering community leadership is particularly important for disrupting climate change narratives that consistently portray marginalized communities as victims, lacking the authority and knowledge to develop their own solutions.

Recently my colleague Sibyl Diver, a research scientist and community-engaged scholar with whom I teach a foundational Introduction to Environmental Justice course at Stanford University, and I wrote an article that uses environmental justice frameworks to map out a process for achieving more inclusive science communication. We hope that this process might train the next generation of science communicators to interrupt inequities based on class, gender and other social positions.

Viewing science communication through an environmental justice lens asks science communicators to 1) become aware of their own positionality and partial perspectives before and during the research process, 2) name sources of inequity that arise from uneven power relations, and 3) find intersections with initiatives that are rooted in the experiences of disadvantaged communities.

In our own class, we sought to teach future scientists how to do this by adding missing perspectives to scientific knowledge production by inviting leaders from diverse and marginalized communities to teach us; increasing the social relevance of scientific findings by asking our students to center the concerns and insights of marginalized communities in their research; and encouraging collective action to address equity concerns and achieve a healthier society for all.

Why is this important? Environmental Justice scholars have long shown, it is precisely such attention to the politics, ethics, and structural inequities surrounding our science that will enable a more inclusive understanding of environmental problems. And by expanding our worldview, we can better evaluate multiple policy interventions that consider social equity issues alongside environmental protections.

So how does one actually do this in their environmental writing? We started by asking our writers to reflect on their own positionality as part of the research and writing process. What personal/professional experiences inspire you to ask the questions you do? How might your identities influence the way you interpret and select your sources? Or the way you might question them? (e.g., what do you notice is missing from the conversation? What narratives are NOT included?) What affordances are you offered by your positionality? What particular vantage point do you have that is unique from others? What are your blindspots? Who are the impacted communities in this case? How will you learn from their voices?

We paid keen attention to centering voices from communities of color and other marginalized groups. By challenging dominant mainstream framing in environmental science that does not include scholarship by persons of color, this approach provided a more complete knowledge of the uneven power relations and discriminatory practices driving environmental problems, and an entry point for students from more privileged backgrounds into challenging social justice issues. It also enabled students of color and other marginalized students, some of whom were from the communities we were reading about, to see their own selves reflected back to them—an important consideration for science communicators who seek to build trust with a broader audience.

Relatedly, we invited EJ leaders to guest teach on a range of issues, including climate justice, food justice, queer ecologies, Afrofuturism, Indigenous knowledge, toxic waste exposures, among others. By having frontline EJ leaders as our teachers we disrupted traditional notions of expert knowledge production in environmental science. Students learned best practices for building more inclusive science communication through listening to their unique stories, and their strategies, especially community-led resilience in the face environmental disparities.

Then came the opportunity to practice with our own writing. Students chose to write about diverse topics ranging from case studies of Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs) as alternative energy providers, to analyses of divestment campaigns across college campuses and food justice organizations in inner cities, to exploring the role of the Silicon Valley tech community in perpetuating environmental injustice. Their geographic locations were also diverse, covering fracking in Pennsylvania, water justice in Michigan, housing rights in North Carolina, and public health in Hawaii, Alaska, and Oakland and Los Angeles, California, to name a few.

To encourage a more inclusive approach to science communication, students had to center community voices, and consider who counted as an authority on their topic and why. This challenged traditional academic notions of expertise and created space for students to center different kinds of authority, particularly the voices of impacted communities. We also asked them to identify their intended audience, and which genre of media would be most effective in reaching that audience. Students needed to consider the most effective language to engage their intended audience, the sociopolitical context of their research, and the real world applications for scientific findings.

Perhaps one of the most important conclusions Sibyl and I came to while writing about this experience is that incorporating environmental justice into science communication does more than support inclusive communication for marginalized communities. Rather, it benefits all people. First, by including the concerns and insights of marginalized communities as part of science communication, we increase the social relevance of scientific findings. Second, by communicating scientific problems in a way that connects with more diverse communities, we invite these communities to participate in scientific knowledge production, and thereby add important experiences and perspectives to a career field that has historically not been very diverse. This intervention breaks down hierarchies to encourage a more complete understanding of the world and contributes to building a healthier society for all, an act that has never been more urgent.

Emily Polk, PhD, teaches climate change communication courses at Stanford University. Prior, she worked as a global human rights and environment–focused writer, editor, and teacher. Her book Communicating Global to Local Resiliency focuses on community-led responses to climate change and her other climate and sustainability related work has been published in global anthologies, peer-reviewed journals, and magazines.

Her recent article “Communicating Climate Change: What Went Wrong, How Can We Do Better” was published in the Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change, (Springer 2018). Her article with Sibyl Diver, “Situating the Scientist: Creating Inclusive Science Communication Through Equity Framing and Environmental Justice” is forthcoming in Frontiers in Communication.

Please consider joining Emily in Chamonix France this summer where she will be offering a climate change communication workshop and retreat in collaboration with author and conservation scientist Dr. Lauren Oakes and CREA, a research center for alpine ecosystems. More information: https://creamontblanc.org/en/climate-comms

Dr. Sibyl Diver is a researcher at Stanford in the Department of Earth System Science. She studies natural resource governance with Indigenous communities in the Pacific Northwest, and takes a community-engaged research approach to her work. Together with Dr. Emily Polk, she co-teaches the first comprehensive introductory environmental justice class at Stanford.

DATE

December 17, 2019AUTHOR

Emily PolkSibyl Diver

SHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Future Earth Members Selected as Experts for IPCC Special Report on Cities

Sign the COP28 statement. The Science is Clear: We Need Net Zero Carbon Dioxide Emissions by 2050.

Unmasking our Carbon and Climate Futures