Principles for Successful Knowledge Co-production for Sustainability Research

Centuries of science has created a phenomenally successful mechanism for producing knowledge, and our understanding of the world has improved with each installment of new evidence. In this traditional model of knowledge generation, the emphasis has been on scientists alone to identify an issue or problem, carry out the research and then deliver the knowledge to society.

But messy and complex problems, particularly those relating to climate change, ecological crises, and poverty alleviation, can’t be dealt with in this way. This is why researchers and practitioners are turning to “co-production of knowledge” as a promising approach mechanism that ensures scientific integrity while exploring solutions with those who need them.

Co-production of knowledge is not exactly new. It has been around for four decades or more, and has often focused on small-scale fisheries, or agricultural areas. The approach is now shifting from the margins of scientific practice towards the center. Researchers have been cast by its spell as organizations like Future Earth promote it as an important way for science to confront the sustainability challenges of the 21st century.

However, knowledge co-production is not easy. The ways in which it is defined and put into practice are diverse, and sometimes contradictory. While this contributes to the creative use of the approach, it severely limits our ability to compare and learn from the outcomes and thus improve practice.

We wanted to address this increasingly problematic gap. In a recent paper in Nature Sustainability we mobilized the experiences and perspectives of 36 leading researchers and practitioners and collectively define knowledge co-production for sustainability research as:

“an iterative and collaborative processes involving diverse types of expertise, knowledge and actors to produce context-specific knowledge and pathways towards a sustainable future.”

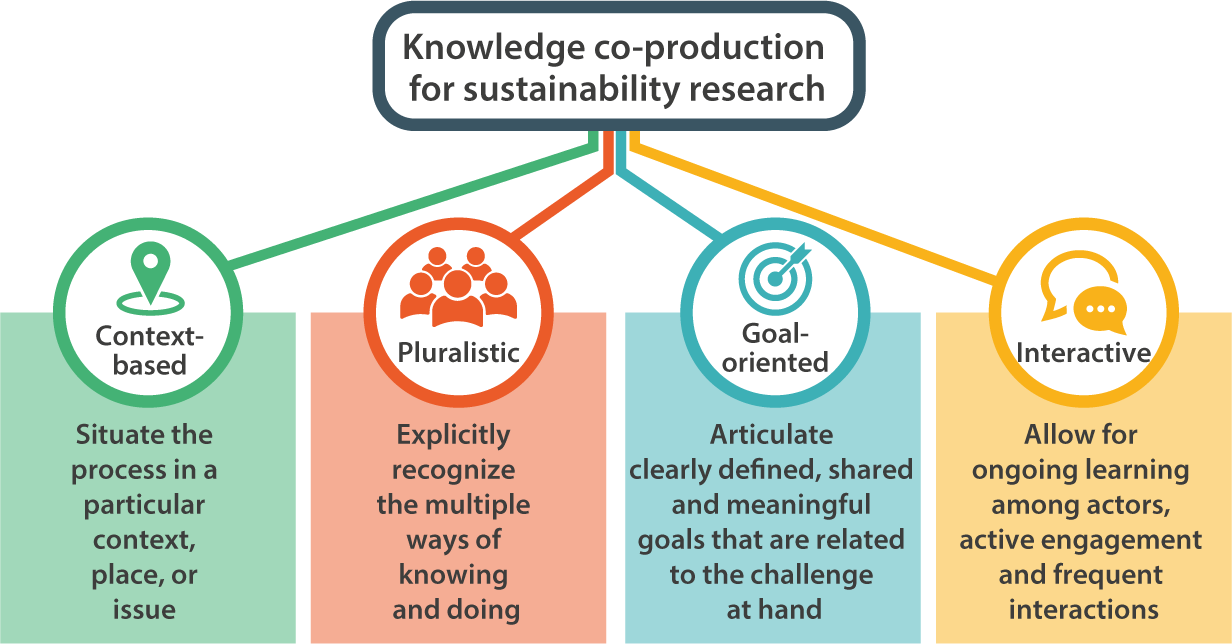

We argue that successful knowledge co-production is more likely if it adheres to the four following principles:

- Context-based: This means understanding how a challenge emerged, how it is affected by its particular social, economic, and ecological contexts, and the different beliefs and needs of those affected by it.

- Pluralistic: The process should explicitly recognize a range of perspectives, knowledge, and expertise and consider gender, ethnicity and age in developing the project.

- Goal-oriented: This implies articulating clearly defined, shared, and meaningful goals that are related to the challenge at hand.

- Interactive: It is critical to allow for ongoing learning among actors, active engagement, and frequent interactions.

Practical guidance on how to engage in meaningful co-production.

We didn’t want this to be a purely theoretical exercise. In fact, we strongly felt from the onset that we wanted to provide concrete practical guidance and insights, based on our own experiences, to researchers and practitioners trying to set up their own co-production processes. By digging deeper in three case-studies – from Columbia, Papua New Guinea and Canada – we explicitly highlight some of the practical nuances in applying the principles.

For example, there are many types of advance work – such as building trust and revealing tensions and expectations within the team – that are needed before the “knowledge-generation” part begins. In fact, this advance work can really stretch back in time, and many knowledge co-production processes are often dependent on past legacies. This includes earlier collaborations among some of the scientists on the team, conceptual insights obtained in earlier projects, long established research sites, or earlier interactions with local stakeholders.

Furthermore, successful knowledge co-production processes often require a “political window of opportunity” or “hooking point” to provide a tangible starting place for the process. In Colombia, for example, a national process to revise Colombian protected areas, together with international commitments made at the UNFCCC COP21, provided windows of opportunity for a co-production process focusing on new ways of understanding and managing Colombian protected areas in the face of ongoing ecological change.

Knowledge co-production in the Anthropocene

Knowledge co-production processes have predominantly involved teams of academics and non-academics working at local to regional level. Now there is growing interest in how to apply this approach at global or regional scale. This is increasingly important, given the dynamics of the Anthropocene – where local contexts are influenced by multiple drivers at larger scales, and have complex connections to other places. Approaches to knowledge co-production for a sustainable Anthropocene may entail new alliances with a different suite of non-academic actors. For example, in the paper we highlight a major international collaboration between the largest seafood companies and researchers to attempt to rethink the global fishing industry (www.keystonedialogues.earth).

We welcome the rapid gain in currency that knowledge co-production has witnessed in recent decades. However, co-production on its own is not enough to bring about more sustainable outcomes. It is also important to nurture deep shifts in worldviews that “reconnect people to nature.” Incentive structures that primarily reward disciplinary science that does not engage with society need to be radically overhauled. Nevertheless, we hope that our four principles will guide and inspire researchers, practitioners, programme managers, and funders seeking to engage in co-produced sustainability research. They should not be seen as a definitive list, and we hope that they serve as a stimulus for further discussion and their continued refinement.

A version of this post can also be found at the London School of Economics and Political Science Impact Blog.

“Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research” was published in Nature Sustainability on 20 January 2020. (DOI: 10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2)

About the authors

Dr. Albert Norström is the Deputy Director of the Guidance for Resilience in the Anthropocene: Investments for Development (GRAID) programme which is hosted by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. His current work spans the social-ecological dynamics of ecosystem services, the development of positive social-ecological visions for sustainable futures and delivering better frameworks to understand what is meant by knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Find Albert on Twitter @AlbertNorstrm.

Dr. Chris Cvitanovic is a Transdisciplinary Marine Scientist working to improve the relationship between science, policy and practice to enable evidence-informed decision-making for sustainable ocean futures. In doing so Chris draws on almost ten years of experience working at the interface of science and policy for the Australian Government Department of Environment, and then as a Knowledge Broker in CSIROs Climate Adaptation Flagship. Find Chris on Twitter @ChrisCvitanovic.

Dr. Marie F. Löf is a Research Scientist at Stockholm University Baltic Sea Centre, Sweden, focusing on ecotoxicology, science communication and knowledge exchange, both from an applied and a research perspective. Both she and the Baltic Sea Centre work to increase the knowledge exchange between science and decision-makers, and to enhance the impact of scientific knowledge on policy and practice, where knowledge co-production is an important approach. Find Marie on Twitter via @lof_marie.

Dr. Simon West is a postdoctoral researcher in sustainability science at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. His research explores the ways in which people generate, share and use knowledge in relation to complex social-ecological issues. He is currently engaged in two collaborative research projects: working with the Arafura Swamp Rangers in Northern Australia to co-produce an intercultural monitoring and evaluation system, and with the Village of Wainwright in North Slope Alaska to explore human responses to ecological regime shifts. Find Simon on Twitter @sim_patrickwest

Dr. Carina Wyborn is the research advisor at the Luc Hoffmann Institute and a research fellow at the W.A. Frankie College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana. She is an interdisciplinary social scientist, who works on the science policy interface in complex sustainability challenges. Her research focuses on anticipatory governance and the capacities to make decisions in the context of uncertain and contested socio-environmental change. Find Carina on Twitter @rini_rants.

DATE

January 21, 2020AUTHOR

Albert NorströmDr. Carina Wyborn

Dr. Chris Cvitanovic

Dr. Marie Löf

Dr. Simon West

SHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Sustainability Research and Innovation Congress 2024

Help Develop a Sustainability Short Course Piloted at SRI2023

Open Call: Charting the Course for the Next Decade of Sustainability Research and Innovation